Background#

Policy gradient methods directly optimize the expected return by taking gradients of the objective:

where is the advantage estimate. The choice of advantage estimator determines the bias-variance tradeoff, which is the central theme of this assignment. We start with the full trajectory return (high variance), add reward-to-go (exploit causality), subtract a learned baseline (reduce variance further), and finally use GAE-λ (smoothly interpolate between TD and Monte Carlo).

1. Vanilla Policy Gradients on CartPole#

Eight experiments on CartPole-v0: all combinations of {small batch (1000), large batch (4000)} × {no tricks, reward-to-go, advantage normalization, both}.

# Small batch (b=1000): cartpole, cartpole_rtg, cartpole_na, cartpole_rtg_na

# Large batch (b=4000): cartpole_lb, cartpole_lb_rtg, cartpole_lb_na, cartpole_lb_rtg_na

./experiment1.sh

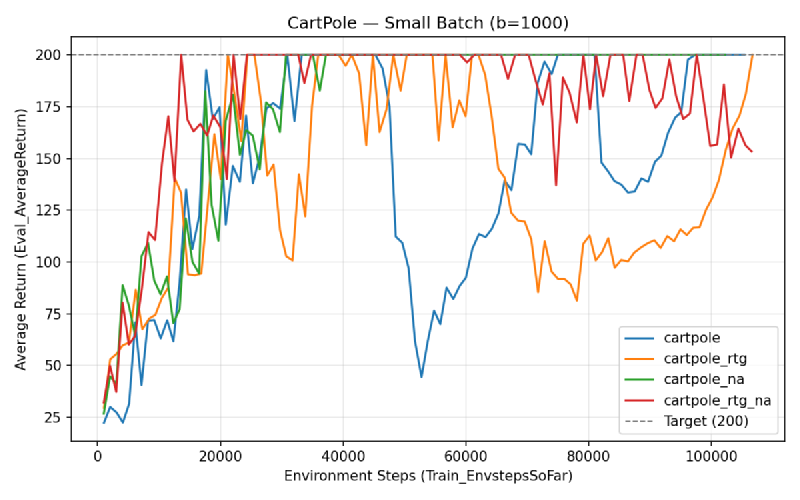

Small Batch (b=1000)#

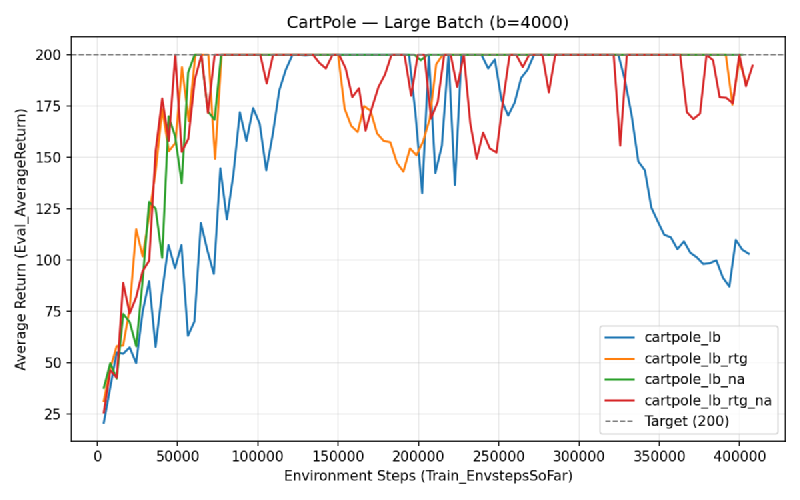

Large Batch (b=4000)#

Questions#

Which value estimator has better performance without advantage normalization? Reward-to-go looks slightly better, though the difference is small in the small batch case.

Why is reward-to-go generally preferred? It has lower variance because it uses causality — rewards earned before a decision are irrelevant noise for that decision’s gradient.

Did advantage normalization help? Yes, quite a bit. The average reward reaches 200 quicker and stays more stable once there.

Did the batch size make an impact? Yes. Smaller batches converge faster in wall-clock iterations but are less stable after convergence. Larger batches trade speed for stability.

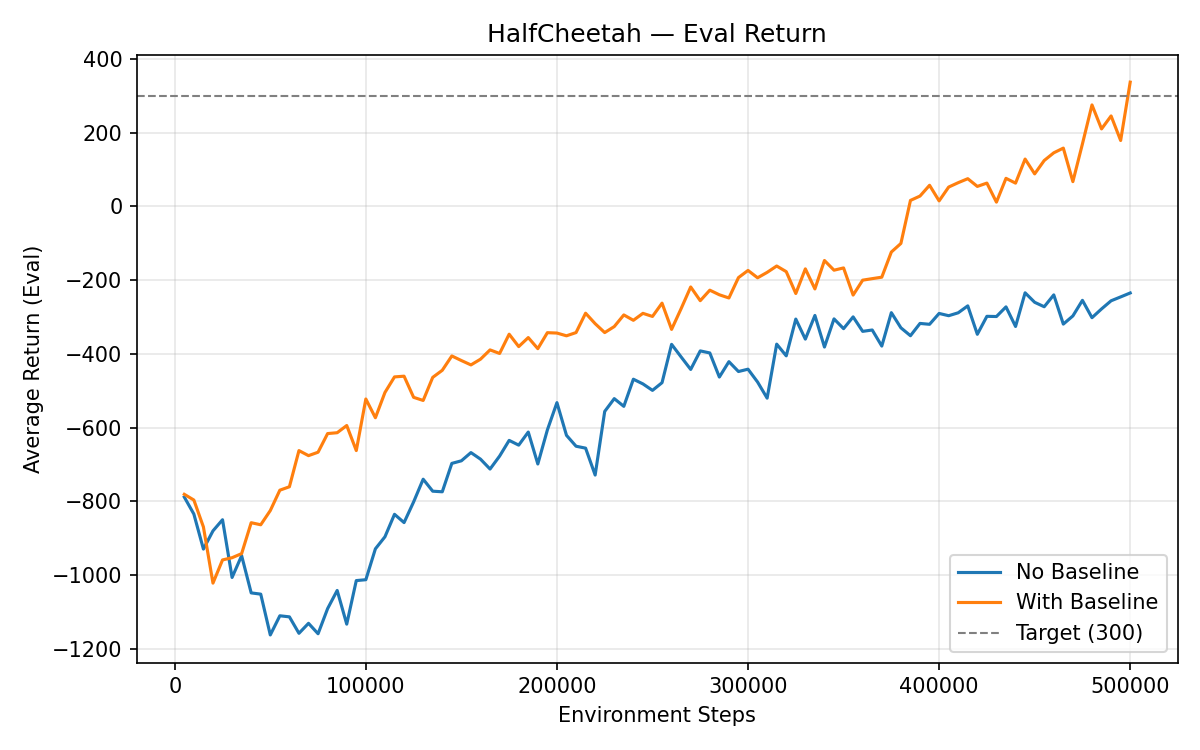

2. Neural Network Baselines on HalfCheetah#

A learned value function serves as a state-dependent baseline. The advantage becomes:

# No baseline vs baseline (bgs=5) vs baseline (bgs=2)

./experiment2.sh

Effect of Reducing Baseline Gradient Steps (bgs=2 vs 5)#

I changed bgs from 5 to 2:

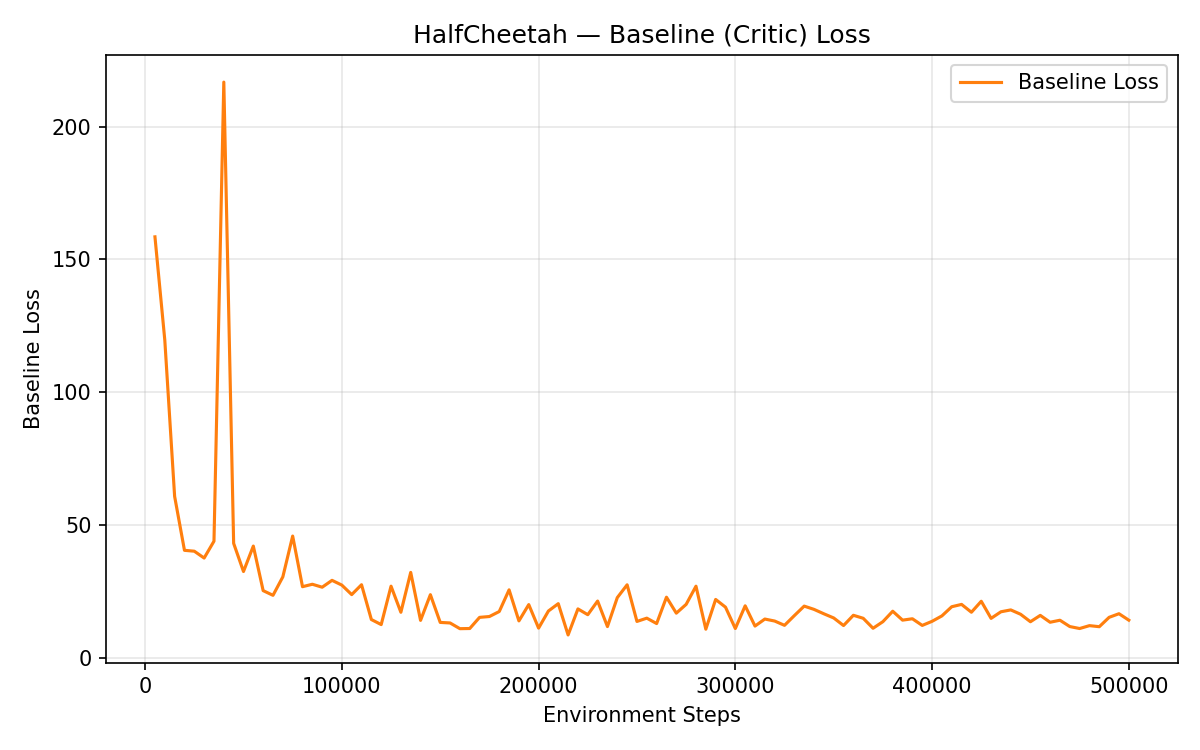

(a) The baseline learning curve becomes much more unstable — large spikes and a big uptrend toward the end, since 2 gradient steps aren’t enough to fit the value function well each iteration.

(b) The eval average return decreases significantly early on (~1000 steps) due to the high baseline loss. When the baseline loss spikes up later, the eval return drops again — a bad baseline actively hurts the policy.

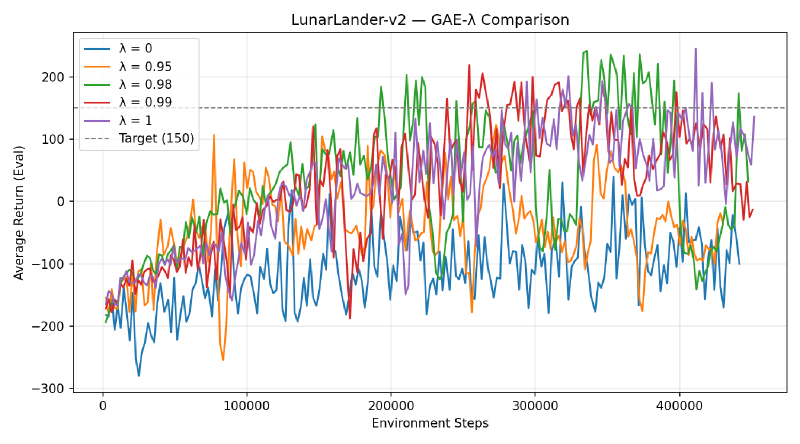

3. GAE-λ on LunarLander#

Generalized Advantage Estimation smoothly interpolates between TD(0) (λ=0, low variance / high bias) and Monte Carlo (λ=1, high variance / low bias):

where .

# λ ∈ {0, 0.95, 0.98, 0.99, 1}

./experiment3.sh

Questions#

What does λ = 0 correspond to? Pure TD(1) — very low variance but high bias. The advantage estimate is just .

What about λ = 1? Full Monte Carlo returns — low bias but high variance.

In LunarLander, intermediate values of λ (0.95–0.99) perform well. λ = 0 underfits due to bias from value function errors, but λ = 1 doesn’t do too bad.

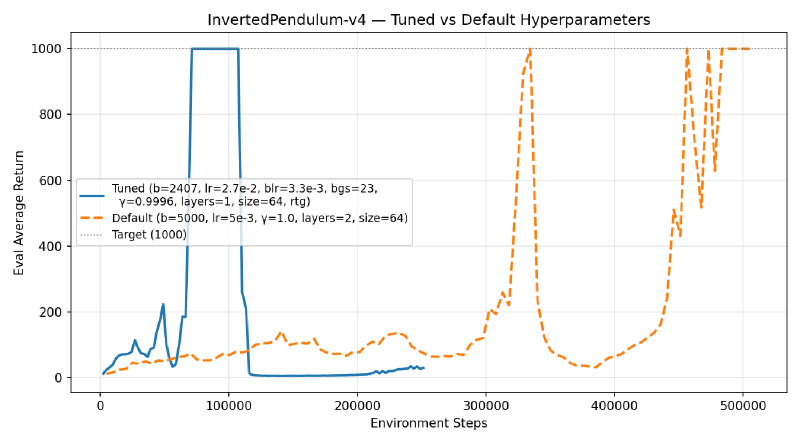

4. Hyperparameter Tuning on InvertedPendulum#

The default settings take ~328K env steps to reach max reward (1000). The goal: get there within 100K steps.

Approach#

I ran a random search (20 trials) sampling learning rates and batch size in log-space, then a second round of 20 trials centered on the best configuration from round 1.

Best Hyperparameters#

uv run src/scripts/run.py \

--env_name InvertedPendulum-v4 \

-n 100 \

-b 2407 \

-eb 1000 \

--learning_rate 2.7e-02 \

--baseline_learning_rate 3.3e-03 \

--baseline_gradient_steps 23 \

--discount 0.9996 \

--n_layers 1 \

--layer_size 64 \

--use_reward_to_go \

--exp_name pendulum_best

Random hyperparameter sweep code

"""Random hyperparameter search for InvertedPendulum-v4."""

import subprocess

import numpy as np

NUM_TRIALS = 20

GROUP = "pendulum_sweep_v2"

RNG = np.random.default_rng(123)

def log_uniform(low, high):

return float(np.exp(RNG.uniform(np.log(low), np.log(high))))

def log_uniform_int(low, high):

return int(round(log_uniform(low, high)))

def perturb_log(center, factor=3.0):

"""Sample log-uniformly within [center/factor, center*factor]."""

return log_uniform(center / factor, center * factor)

def perturb_log_int(center, factor=3.0, low=1, high=None):

val = int(round(perturb_log(center, factor)))

val = max(val, low)

if high is not None:

val = min(val, high)

return val

for i in range(NUM_TRIALS):

batch_size = perturb_log_int(2653, factor=2.0, low=500)

rtg = RNG.choice([True, False])

blr = perturb_log(9.8e-3)

bgs = perturb_log_int(16, factor=2.0, low=1, high=30)

discount = 1.0 - perturb_log(1.0 - 0.9983, factor=5.0) # perturb around 0.9983

discount = min(discount, 0.9999)

lr = perturb_log(2.8e-2)

n_layers = int(RNG.integers(1, 3, endpoint=True))

layer_size = int(RNG.choice([16, 32, 64]))

tag = (

f"b{batch_size}_lr{lr:.1e}_blr{blr:.1e}"

f"_bgs{bgs}_d{discount:.4f}"

f"_l{n_layers}_s{layer_size}"

f"{'_rtg' if rtg else ''}"

)

exp_name = f"pendulum_{tag}"

cmd = [

"uv", "run", "src/scripts/run.py",

"--env_name", "InvertedPendulum-v4",

"-n", "100",

"-b", str(batch_size),

"-eb", "1000",

"--learning_rate", f"{lr}",

"--baseline_learning_rate", f"{blr}",

"--baseline_gradient_steps", str(int(bgs)),

"--discount", f"{discount}",

"--n_layers", str(n_layers),

"--layer_size", str(layer_size),

"--exp_name", exp_name,

"--group", GROUP,

]

if rtg:

cmd.append("--use_reward_to_go")

print(f"\n{'='*60}")

print(f"Trial {i+1}/{NUM_TRIALS}: {exp_name}")

print(f"{'='*60}")

subprocess.run(cmd, check=True)

The tuned run reaches 1000 at ~71K env steps — a 4.5x speedup over defaults.

What Mattered#

- Learning rate was the most impactful. The default 5e-3 was too conservative; 2.7e-2 converged much faster. InvertedPendulum is simple enough that aggressive updates don’t destabilize training.

- Reward-to-go consistently helped — the best runs all had it enabled.

- Network architecture mattered less than expected. A single hidden layer of 64 units beat deeper/wider nets, suggesting a simple value function suffices for this task.

- Baseline gradient steps (23) — more fitting steps stabilized advantage estimation, paired with a lower baseline LR (3.3e-3 vs default 5e-3) to avoid overfitting.

- Batch size (~2400) balanced gradient quality with iteration speed.

- Discount factor (0.9996) — close to 1.0 but not exactly; unclear if this is meaningful or just noise from the random search.

Key Takeaways#

- Reward-to-go should always be used.

- Baselines reduce variance significantly but need enough gradient steps to be accurate; a bad baseline is worse than no baseline.

- GAE-λ provides a nice knob for bias-variance tradeoff.

- Hyperparameter tuning can yield big sample efficiency gains — 4.5x on InvertedPendulum from random search.

- Random search in log-space is a simple but effective tuning strategy for continuous hyperparameters.